by Kenton Turk

Dziga Vertov’s legendary and highly influential 1929 wordless documentary Man With A Camera receives a tribute and update at once with Michael Nyman’s attempt at “a truly international absolute language”, the original’s stated intention. Where Vertov’s camera captured life in Soviet cities only, Nyman is able to take the aim one step further, reflecting our modern world: here, the locales themselves give evidence of today’s accepted international interaction. 26 countries and territories are listed in the credits, and Nyman’s camera moves as freely between continents as it does between social classes, activities and cinematic devices. What appears at times to be haphazard collage shows abundant evidence of clever segues that imply plays-on-words or various views of a single subject.

The title’s tongue-in-cheek take on the original foreshadows the sly playfulness Nyman displays throughout. The film leads with the original’s Russian credits, faithfully translating its aims and veering only when names of original collaborators are to be replaced with those contributing to this work. The opening scene is a filmic tribute to the original, with Vertov’s cameraman atop a seemingly huge camera in split screen with a modern boom-mounted camera regarding a phalanx of press photographers. The latter camera will resurface like a symphonic theme, at times intrusively, at others as a ghostly superimposition. From here, we are treated to his vision without losing sight of the kudos due the original. In a series of further split screen shots scattered about the film displaying Vertov’s work to the left, we are continually reminded of the film’s comparative nature: Vertov’s track sweeper sidles up beside Nyman’s bullring track, someone feeling eggs is seen next to someone feeling fruit, black and white film frames are shown beside a digital photo album, people rushing to cross a street next to an old man struggling to do the same, a telephone switchboard edges up to a Nokia delivery truck, in each instance, the monochromatic contrasting with full colour. The device does not lean on the original, but rather includes it as a part of the sum of what we witness today.

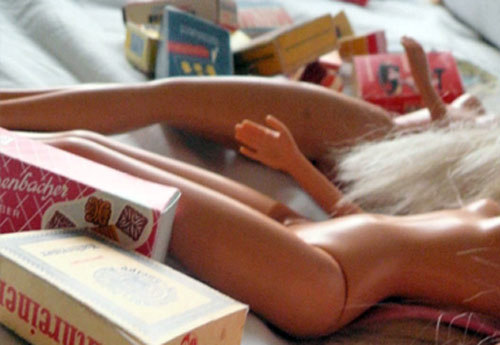

Utilizing his own 2002 BFI-commissioned soundtrack to the original throughout, Nyman proceeds to lead us through a world of personal imagery, showing a predilection for recurring signposts. Most notably, dolls appear throughout, in all forms and in various frames of reference, from baby dolls wrapped in plastic following bridal portraits to Barbie dolls dressed for airline service preceding a still of a stewardess’s legs behind a “Safety on board” warning. Industrial processes and workspaces, sport disciplines and means of transport, particularly trams, also abound.

Tragic scenes married to less tragic ones, such as a car bombing and its victims juxtaposed against examinations of a collection of miniature emergency vehicles only to jump back to actual crises, imply an ability to reference a situation from varying perspectives as well as a certain dark humour. The straightforward variety is also employed. We note with amusement when subjects are unsure of being watched, and are allowed guiltless voyeurism as we spy on a man picking his nose. The unnoticed is sometimes revisited for comic effect: a full shot of plastic- covered automobiles is later re-examined in close-up, with the protuberance of a car mirror so wrapped bearing stark resemblance to a condom-sheathed bulge.

Nyman’s best sequences are those showing wit in making connections. Here he demonstrates awareness of the rapid associations our brains make. An electronic billboard with the name of Mexican soccer star “Israel Castro” is followed by a picture of an imam and an Iranian sport team. A shot of a man plugging his ears precedes various scenes of “playing”: first piano, then backgammon, then a toy xylophone followed by a full-sized one. A scene of a barber at work leads to a drawing of bald heads, then a bald androgynous couple, razors and scissors being sharpened, photo session preparation, and finally hedge clippers and a little girl observing the hedge-trimming while fondling her own tresses. In one of the best, scenes filmed at Ground Zero in New York are followed by barbed wire barriers and (in perhaps the film’s best visual association) a bird apparently flying “into” Berlin’s Fernsehturm in a shot that is eerily reminiscent of “9/11” footage.

A concerted effort is made throughout to include Vertov’s many cinematic innovations and employed techniques, culminating in the final scenes, the film’s most frenetic. In a Koyaanisqatsi-style escalation, we are taken through many of these in dizzyingly fast succession, all paraded out for a last look: simultaneously focused and unfocused frames, multiple images, time lapse photography, split screen, Dutch (or tilted) angles, superimposition, extreme close-ups, diagonally split images, jump cuts and more, the various techniques concentrated on performers and performing spaces, cameras and spectators. In the final shot, the red carpet press photographers of the opening are inserted into a camera’s lens, turning the tables, as it were. Observers become the observed.

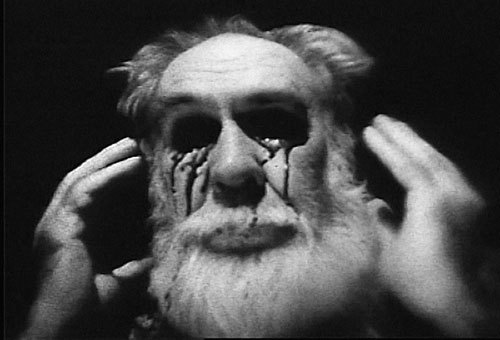

Nyman references not only Vertov’s, but also his own forays into film. The shadowed drapery of his Witness I makes an early appearance, to be followed later in the film by the same film’s haunting faces. Sequences from other Nyman offerings will also later vie for attention: the inept but unperturbed passenger of Tieman can be seen; the “Wanted” poster of Searching For Bacon briefly appears. Nyman himself, not to be forgotten, shows up Hitchcock-like in a few scenes. Vertov’s shot of a Russian-language “Gorky” banner spanning a street shares the screen with a “Nyman” banner doing the same; later, electronic ribbon text announces his appearance at the Toronto International Film Festival. We see him from behind early on, later as a reflection, a man with a camera. About halfway through the film, we spy a poster with the slogan “Your sight is precious”; over it is Nyman’s own reflection in glass while he brings the shot in with a slow zoom. An appropriate way to sum up the film, one thinks.

Can’t make this event?

This screening will also occur on: