NOT BOLLYWOOD. INDIA.

Ajitesh Sharma’s “SWEN” in World Premiere at the 9th Berlin International Directors Lounge

by Kenton Turk

What does he know of India who only one India knows? Many-skinned India reveals itself like a bloom shedding petals in the wind, but the world outside sees mostly two of these. Bollywood’s sparkling otherworldliness has captured the eyes and ears of an international audience, and educational documentaries about life’s difficulties in the sub-continent’s over-populated slums perhaps their hearts as well. But trying to grasp India by taking in a Bollywood flick would be like preparing for a trip to New York by visiting Disneyland first. And while poverty and squalor may still much be a part of the world’s fastest-growing population, the future is headed elsewhere.

Ajitesh Sharma’s “SWEN” (taken from “South West East North”) presents drama from an India less often seen internationally. This is the third India, the BRIC nation rising into the world’s top ten economies. Neither poverty-induced misery nor lights-camera-action musical, “SWEN” is people, their interaction and their fates.

Sharma’s association with Directors Lounge is not new. In 2010, DL in its sixth annual outing presented his 44-minute “Visible Bra Straps” in World Premiere. The film went on to many another festival, including Cannes, and was ultimately chosen as India’s official entry into the Asian Pacific Film Awards, the “Oscar” of this emerging region. Its star and perhaps Sharma’s muse, the beautiful Reeth Mazumder, also takes the lead in SWEN. At her side is the similarly attractive Johnny Baweja (aka Gurjot Singh).

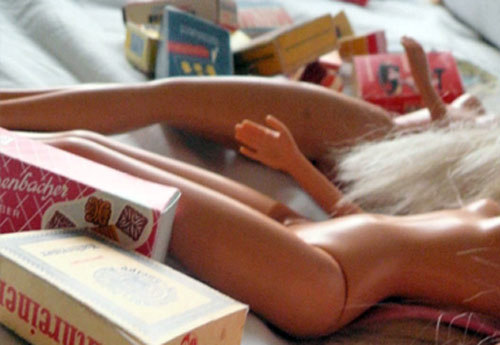

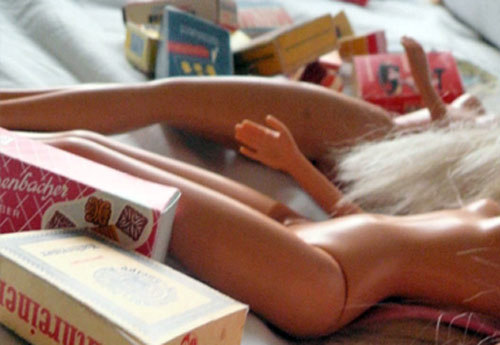

What is new here? More than anything, that India has arrived to take its place there where other countries have tread, but with a cinematic accent and lifestyle all its own. It does well to remember that the film comes from a nation whose first screen kiss in 1978 (!) caused an uproar and a major debate on censorship. As such, the comfortable approach to lovemaking scenes in “SWEN” must be seen as a great leap forward. These sequences are indeed sensuously shot, and conjure up none of the hot-toned, giddy romantic interaction of Bollywood. Rather as the West might know it, but this is still unmistakenly another world. It might feel strange to the viewer to match these images to this country, unless preconceptions can be left at the door. India is, definitely, changing.

If we are ill at ease with an India of unforced mannerism and relative affluence, then maybe because it has been our standpoint to see the great land from colonialists’ or tourists’ eyes, our poor brother full of colour and tradition, but concerned with day-to-day problems of survival. That battle is not over, but much of it is being won, so that Indian cinema can redirect its focus from song-and-dance numbers and predictable plotlines and turn itself to dealing with life and relationships in the modern world. Here, shiny cars are driven, wine is sipped and private pools are swum in while people, in this case four women, discover unexpected connections, all to a soundtrack that is far from what a tour guide would choose to give his customers the feeling of “experiencing” India as they expect it. But make no mistake, this is where India is headed. Sharma offers up a slice of the emerging India today, maybe the accepted picture of India tommorow.

SEE AJITESH SHARMA’S “SWEN” IN WORLD PREMIERE AT [DL9], SUNDAY, FEB. 10, 7:30 pm, ATTENDED BY ITS STARS REETH MAZUMDER AND JOHNNY BAWEJA

Presented by Tripat Paul Aggarwal, First Vice President of International Federation of Film Producers Associations (FIAPF)

Sun 10 the program

the complete program