text-and-communication-based poetry-and-performance video shorts

Lettrétage, Berlin, 17th February 2010

An enthusiastic and growing European audience for the work of U.S. intermedia artist Barbara Rosenthal was treated to an evening with her last month at Lettrétage: Das junge Literaturhaus in Berlin. Included in an hour of about 30 of her quick-paced language and communication text/performance/poetry video shorts were many Berlin premieres, introduced by local film curator Klaus W. Eisenlohr. The full solo programme itself was curated by art historian Nicole Mittenbühlen to include key Rosenthal early videos such as How Much Does the Monkey Remember (1988), Nonsense Conversation (1988), and I Have a New York Accent (1990) plus three world premieres: Feet Handoff, Rules, and Secret Codes.

In Rules (2010), 1min 59sec, a stern series of white and gray onscreen texts in English and German crawls rapidly by to each line’s own grating, but haunting, compelling, menacing sound, created by German sound artist Brandstifter and reprocessed by Rosenthal. Rule 1: There are no rules. Rule 2: Rule 1 may change without notice. Rosenthal lives in Kafka’s world. As the video runs along, the English and German try retranslating each other, try extracting other meanings, try seeking clarification. Her work draws us into interpretation; she shows us what she sees and feels: that rules get imposed on us even when we’re told we may operate in trustful innocence without them, that things are never what they seem, but saying so threatens violence.

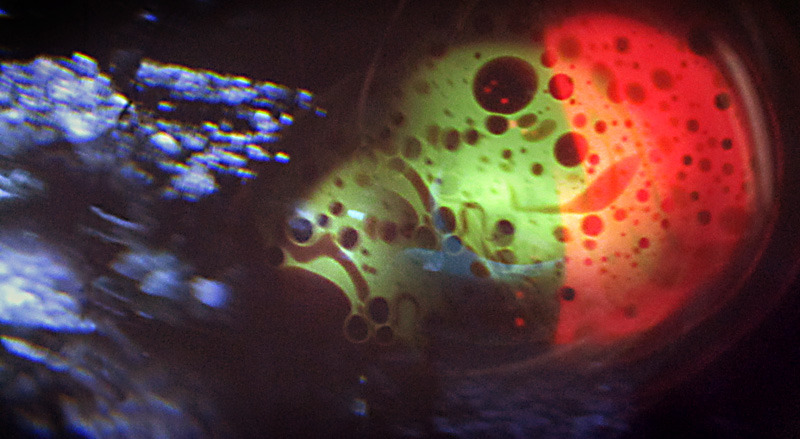

Secret Codes (2010), 4min 35sec, is a text-and-image video that employs familiar Rosenthal graphic techniques such as split screens, stills, color mixed with black and white, patterns, trapezoids, and what she calls “reprised imagery” or “logo images.” In this new video, she uses a grayscale collage of palmprints from a multi-panel print edition she made in 1990, Poodle Dog/Oz House/Aberrant Palms, and a new color collage of her own hands pressed tight against a scanner (as if pressing from behind the screen), and a repeating Yiddish, German, and English text: That which on first glance is alike, on further inspection tells us apart. Here again she has collaborated with a German, Berlin musician RoBeat Schmidt, for a compelling, pounding, rising audio-track. This is surely an investigation into the nature of individuality and its co-valent relationships with language and culture. There is a probable theme here about Jews in Germany, but also about Americans in Europe, and artists in the world: that they may look like everybody else, and seem to fit in, but… This theme, of individuals recognizing their groups, has been investigated by Rosenthal before, such as in Dog Recognition, which for this programme, appeared in English, Russian, and German. In Beijing, she showed it in Chinese.

The curator, Nicole Mittenbühlen drew our attention to the links between these two works Secret Codes (2010) and Dog Recognition (2005-10). Although they both show onscreen text and use a series of stills and somewhat abstract sound (her dog barking in Dog Recognition), they are very different from each other in mood and technique (Dog Recognition is made with line drawings). Yet both demonstrate Rosenthal’s relentless consistency and the continued relevance of her existential subject matter: the struggle for meaning within human existence, the assertion of individuality and personality (even more than ethnology) as identity, and things like handprints and brainscans, images she calls “the markers” for and balances between our differences and our kinships.

There is perhaps no better place than here in Berlin, just down the road from Humboldt University, with its esteemed history of philosophical and psychological discourse, to parse the work of this Jewish New York artist and to define our own. A dedicated pioneer in the medium of video, and especially in the combined media of performance-text-installation-audio-video, her works from the eighties, despite preserving by (although perhaps through the enhancement of) digital remastering, pulse with the urgency and excitement of the cut and paste, stop motion, the controlled directedness of placing image with text, and of skewering literal meanings, that are the procedural hallmarks of Rosenthal’s a practice known for its life-art mix. When asked at Lettrétage about life-references, she said that the inspiration for both Rules and Secret Codes came during a stressful personal relationship. In Klaus W. Eisenlohr’s introduction, he made the point that Rosenthal’s ideas, personal/social politics, mix of media, and early combination of print and electronic forms, are all fresh and immediate, and speak of contemporary issues to a contemporary audience.

This exhilarating selection of communication and text-based videos by Barbara Rosenthal spanning three decades offered both retrospective and preview in which her time-line of works rolled out and back upon itself, twisting dates and techniques and laminating innovation with revision. Working with sound artists rather than with appropriated music, as she had in the past, adds a new murmur of dialogue, as well. The flame-haired avatar now makes her work world-wide, so her life-based scenes and casts are changing, too. The gradual disappearance of her now-grown family and of the New York audial backgrounds ubiquitous to her earlier works is now replaced by new places and relationships, less easy to identify. Unrevealed or even named, they nonetheless act as ignition for works that seem more open to her audience, that now invite us in and encourage us to recognize ourselves as much as we do the artist. Although it’s always fun to guess the autobiography behind the art, it is not necessary to know her inspiration for it in order for us to be inspired by it.

As piercing in their observations as anything that has gone before, such as Rosenthal’s set of aphorisms, Provocation Cards, which she showed earlier this year in Prague, this video selection reaches us more personally, like her You & I Cardgame, recently purchased by the Tate. Europeans are feeling very connected to her work. The trajectory of it is directly from her-self to we-self. We enter her mind-set: her art insists that we engage, question, think, act! She says we have always been in this together, now it feels like we are.

(by Clare Carswell)

photo by Klaus W. Eisenlohr

Full Solo program: “EXISTENTIAL WORD PLAY”

34 language and communication text/performance/poetry short videos in 68 minutes

including 3 WORLD PREMIERES

WEDNESDAY (MITTWOCH), 17 FEB., 7pm

at LETTRÉTAGE

Lettrétage: Das junge Literaturhaus in Berlin

Methfesselstr. 23-25; 10965 Berlin (Kreuzberg)

tel: 030.692.45.38

Full Program, in Order: Lettering Too Big, Secret Of Life, Nancy And Sluggo, Boy And Father, Boggle, Paths To Follow, Words Backwards, Quotation From Paul Gauguin, This Is A, Dog Recognition, Postcards, Rules, Space And Time, World View, Names And Faces, Siddhartha, Black And Silent, Whispering Confession, Secret Codes, Burp Talk, Daily News, News To Fit The Family, I Have A NY Accent, Lying Diary/Provocation Cards, Semaphore Poems, News Wall, Nonsense Conversation, Society, How Much Does The Monkey Remember, Feet Handoff, Pregnancy Dreams, Handwriting Analysis.

and

Directors Lounge screening:

3 shorts | Barbara Rosenthal

Fri 18th 8 pm

Barbara Rosenthal US

Rules 1 min 2009

International Garbage 03min 38sec 2010

Secret Codes 1 min 30s 2010

In attendance of Barbara Rosenthal